Starting Out

Ready, set, go!

Alright, let’s get started! If

you’re the sort of horrible person who doesn’t read introductions to

things and you skipped it, you might want to read the last section in

the introduction anyway because it explains what you need to follow this

tutorial and how we’re going to load functions. The first thing we’re

going to do is run GHC’s interactive mode and call some function to get

a very basic feel for Haskell. Open your terminal and type in

Alright, let’s get started! If

you’re the sort of horrible person who doesn’t read introductions to

things and you skipped it, you might want to read the last section in

the introduction anyway because it explains what you need to follow this

tutorial and how we’re going to load functions. The first thing we’re

going to do is run GHC’s interactive mode and call some function to get

a very basic feel for Haskell. Open your terminal and type in

ghci. You will be greeted with something like this.

GHCi, version 9.2.4: https://www.haskell.org/ghc/ :? for help

ghci>Congratulations, you’re in GHCI!

Here’s some simple arithmetic.

ghci> 2 + 15

17

ghci> 49 * 100

4900

ghci> 1892 - 1472

420

ghci> 5 / 2

2.5

ghci>This is pretty self-explanatory. We can also use several operators on one line and all the usual precedence rules are obeyed. We can use parentheses to make the precedence explicit or to change it.

ghci> (50 * 100) - 4999

1

ghci> 50 * 100 - 4999

1

ghci> 50 * (100 - 4999)

-244950Pretty cool, huh? Yeah, I know it’s not but bear with me. A little

pitfall to watch out for here is negating numbers. If we want to have a

negative number, it’s always best to surround it with parentheses. Doing

5 * -3 will make GHCI yell at you but doing

5 * (-3) will work just fine.

Boolean algebra is also pretty straightforward. As you probably know,

&& means a boolean and, ||

means a boolean or. not negates a

True or a False.

ghci> True && False

False

ghci> True && True

True

ghci> False || True

True

ghci> not False

True

ghci> not (True && True)

FalseTesting for equality is done like so.

ghci> 5 == 5

True

ghci> 1 == 0

False

ghci> 5 /= 5

False

ghci> 5 /= 4

True

ghci> "hello" == "hello"

TrueWhat about doing 5 + "llama" or 5 == True?

Well, if we try the first snippet, we get a big scary error message!

• No instance for (Num String) arising from a use of ‘+’

• In the expression: 5 + "llama"

In an equation for ‘it’: it = 5 + "llama"Yikes! What GHCI is telling us here is that "llama" is

not a number and so it doesn’t know how to add it to 5. Even if it

wasn’t "llama" but "four" or "4",

Haskell still wouldn’t consider it to be a number. +

expects its left and right side to be numbers. If we tried to do

True == 5, GHCI would tell us that the types don’t match.

Whereas + works only on things that are considered numbers,

== works on any two things that can be compared. But the

catch is that they both have to be the same type of thing. You can’t

compare apples and oranges. We’ll take a closer look at types a bit

later. Note: you can do 5 + 4.0 because 5 is

sneaky and can act like an integer or a floating-point number.

4.0 can’t act like an integer, so 5 is the one

that has to adapt.

You may not have known it but we’ve been using functions now all

along. For instance, * is a function that takes two numbers

and multiplies them. As you’ve seen, we call it by sandwiching it

between them. This is what we call an infix function. Most

functions that aren’t used with numbers are prefix functions.

Let’s take a look at them.

Functions are usually prefix, so

from now on we won’t explicitly state that a function is of the prefix

form, we’ll just assume it. In most imperative languages, functions are

called by writing the function name and then writing its parameters in

parentheses, usually separated by commas. In Haskell, functions are

called by writing the function name, a space and then the parameters,

separated by spaces. For a start, we’ll try calling one of the most

boring functions in Haskell.

Functions are usually prefix, so

from now on we won’t explicitly state that a function is of the prefix

form, we’ll just assume it. In most imperative languages, functions are

called by writing the function name and then writing its parameters in

parentheses, usually separated by commas. In Haskell, functions are

called by writing the function name, a space and then the parameters,

separated by spaces. For a start, we’ll try calling one of the most

boring functions in Haskell.

ghci> succ 8

9The succ function takes anything that has a defined

successor and returns that successor. As you can see, we just separate

the function name from the parameter with a space. Calling a function

with several parameters is also simple. The functions min

and max take two things that can be put in an order (like

integers!). min returns the one that’s lesser and

max returns the one that’s greater. See for yourself:

ghci> min 9 10

9

ghci> max 100 101

101Function application (calling a function by putting a space after it and then typing out the parameters) has the highest precedence of them all. What that means for us is that these two statements are equivalent.

ghci> succ 9 + max 5 4 + 1

16

ghci> (succ 9) + (max 5 4) + 1

16However, if we wanted to get the successor of the product of numbers

9 and 10, we couldn’t write succ 9 * 10 because that would

get the successor of 9, which would then be multiplied by 10. So 100.

We’d have to write succ (9 * 10) to get 91.

If a function takes two parameters, we can also call it as an infix

function by surrounding it with backticks. For instance, the

div function takes two integers and does integral division

between them. Doing div 92 10 results in a 9. But when we

call it like that, there may be some confusion as to which number is

doing the division and which one is being divided. So we can call it as

an infix function by doing 92 `div` 10 and suddenly it’s

much clearer.

Lots of people who come from imperative languages tend to stick to

the notion that parentheses should denote function application. For

example, in C, you use parentheses to call functions like

foo(), bar(1) or baz(3, "haha").

Like we said, spaces are used for function application in Haskell. So

those functions in Haskell would be foo, bar 1

and baz 3 "haha". So if you see something like

bar (bar 3), it doesn’t mean that bar is

called with bar and 3 as parameters. It means

that we first call the function bar with 3 as

the parameter to get some number and then we call bar again

with that number. In C, that would be something like

bar(bar(3)).

Baby’s first functions

In the previous section we got a basic feel for calling functions. Now let’s try making our own! Open up your favorite text editor and punch in this function that takes a number and multiplies it by two.

doubleMe x = x + xFunctions are defined in a similar way that they are called. The

function name is followed by parameters separated by spaces. But when

defining functions, there’s a = and after that we define

what the function does. Save this as baby.hs or something.

Now navigate to where it’s saved and run ghci from there.

Once inside GHCI, do :l baby. Now that our script is

loaded, we can play with the function that we defined.

ghci> :l baby

[1 of 1] Compiling Main ( baby.hs, interpreted )

Ok, one module loaded.

ghci> doubleMe 9

18

ghci> doubleMe 8.3

16.6Because + works on integers as well as on floating-point

numbers (anything that can be considered a number, really), our function

also works on any number. Let’s make a function that takes two numbers

and multiplies each by two and then adds them together.

doubleUs x y = x*2 + y*2Simple. We could have also defined it as

doubleUs x y = x + x + y + y. Testing it out produces

pretty predictable results (remember to append this function to the

baby.hs file, save it and then do :l baby

inside GHCI).

ghci> doubleUs 4 9

26

ghci> doubleUs 2.3 34.2

73.0

ghci> doubleUs 28 88 + doubleMe 123

478As expected, you can call your own functions from other functions

that you made. With that in mind, we could redefine

doubleUs like this:

doubleUs x y = doubleMe x + doubleMe yThis is a very simple example of a common pattern you will see

throughout Haskell. Making basic functions that are obviously correct

and then combining them into more complex functions. This way you also

avoid repetition. What if some mathematicians figured out that 2 is

actually 3 and you had to change your program? You could just redefine

doubleMe to be x + x + x and since

doubleUs calls doubleMe, it would

automatically work in this strange new world where 2 is 3.

Functions in Haskell don’t have to be in any particular order, so it

doesn’t matter if you define doubleMe first and then

doubleUs or if you do it the other way around.

Now we’re going to make a function that multiplies a number by 2 but only if that number is smaller than or equal to 100 because numbers bigger than 100 are big enough as it is!

doubleSmallNumber x = if x > 100

then x

else x*2

Right here we introduced Haskell’s if statement. You’re probably

familiar with if statements from other languages. The difference between

Haskell’s if statement and if statements in imperative languages is that

the else part is mandatory in Haskell. In imperative languages you can

just skip a couple of steps if the condition isn’t satisfied but in

Haskell every expression and function must return something. We could

have also written that if statement in one line but I find this way more

readable. Another thing about the if statement in Haskell is that it is

an expression. An expression is basically a piece of code that

returns a value. 5 is an expression because it returns 5,

4 + 8 is an expression, x + y is an expression

because it returns the sum of x and y. Because

the else is mandatory, an if statement will always return something and

that’s why it’s an expression. If we wanted to add one to every number

that’s produced in our previous function, we could have written its body

like this.

doubleSmallNumber' x = (if x > 100 then x else x*2) + 1Had we omitted the parentheses, it would have added one only if

x wasn’t greater than 100. Note the ' at the

end of the function name. That apostrophe doesn’t have any special

meaning in Haskell’s syntax. It’s a valid character to use in a function

name. We usually use ' to either denote a strict version of

a function (one that isn’t lazy) or a slightly modified version of a

function or a variable. Because ' is a valid character in

functions, we can make a function like this.

conanO'Brien = "It's a-me, Conan O'Brien!"There are two noteworthy things here. The first is that in the

function name we didn’t capitalize Conan’s name. That’s because

functions can’t begin with uppercase letters. We’ll see why a bit later.

The second thing is that this function doesn’t take any parameters. When

a function doesn’t take any parameters, we usually say it’s a

definition (or a name). Because we can’t change what

names (and functions) mean once we’ve defined them,

conanO'Brien and the string

"It's a-me, Conan O'Brien!" can be used

interchangeably.

An intro to lists

Much like shopping lists in

the real world, lists in Haskell are very useful. It’s the most used

data structure and it can be used in a multitude of different ways to

model and solve a whole bunch of problems. Lists are SO awesome. In this

section we’ll look at the basics of lists, strings (which are lists) and

list comprehensions.

Much like shopping lists in

the real world, lists in Haskell are very useful. It’s the most used

data structure and it can be used in a multitude of different ways to

model and solve a whole bunch of problems. Lists are SO awesome. In this

section we’ll look at the basics of lists, strings (which are lists) and

list comprehensions.

In Haskell, lists are a homogenous data structure. They store several elements of the same type. That means that we can have a list of integers or a list of characters but we can’t have a list that has a few integers and then a few characters. And now, a list!

ghci> lostNumbers = [4,8,15,16,23,42]

ghci> lostNumbers

[4,8,15,16,23,42]As you can see, lists are denoted by square brackets and the values

in the lists are separated by commas. If we tried a list like

[1,2,'a',3,'b','c',4], Haskell would complain that

characters (which are, by the way, denoted as a character between single

quotes) are not numbers. Speaking of characters, strings are just lists

of characters. "hello" is just syntactic sugar for

['h','e','l','l','o']. Because strings are lists, we can

use list functions on them, which is really handy.

A common task is putting two lists together. This is done by using

the ++ operator.

ghci> [1,2,3,4] ++ [9,10,11,12]

[1,2,3,4,9,10,11,12]

ghci> "hello" ++ " " ++ "world"

"hello world"

ghci> ['w','o'] ++ ['o','t']

"woot"Watch out when repeatedly using the ++ operator on long

strings. When you put together two lists (even if you append a singleton

list to a list, for instance: [1,2,3] ++ [4]), internally,

Haskell has to walk through the whole list on the left side of

++. That’s not a problem when dealing with lists that

aren’t too big. But putting something at the end of a list that’s fifty

million entries long is going to take a while. However, putting

something at the beginning of a list using the : operator

(also called the cons operator) is instantaneous.

ghci> 'A':" SMALL CAT"

"A SMALL CAT"

ghci> 5:[1,2,3,4,5]

[5,1,2,3,4,5]Notice how : takes a number and a list of numbers or a

character and a list of characters, whereas ++ takes two

lists. Even if you’re adding an element to the end of a list with

++, you have to surround it with square brackets so it

becomes a list.

[1,2,3] is actually just syntactic sugar for

1:2:3:[]. [] is an empty list. If we prepend

3 to it, it becomes [3]. If we prepend

2 to that, it becomes [2,3], and so on.

Note: [], [[]]

and[[],[],[]] are all different things. The first one is an

empty list, the second one is a list that contains one empty list, the

third one is a list that contains three empty lists.

If you want to get an element out of a list by index, use

!!. The indices start at 0.

ghci> "Steve Buscemi" !! 6

'B'

ghci> [9.4,33.2,96.2,11.2,23.25] !! 1

33.2But if you try to get the sixth element from a list that only has four elements, you’ll get an error so be careful!

Lists can also contain lists. They can also contain lists that contain lists that contain lists …

ghci> b = [[1,2,3,4],[5,3,3,3],[1,2,2,3,4],[1,2,3]]

ghci> b

[[1,2,3,4],[5,3,3,3],[1,2,2,3,4],[1,2,3]]

ghci> b ++ [[1,1,1,1]]

[[1,2,3,4],[5,3,3,3],[1,2,2,3,4],[1,2,3],[1,1,1,1]]

ghci> [6,6,6]:b

[[6,6,6],[1,2,3,4],[5,3,3,3],[1,2,2,3,4],[1,2,3]]

ghci> b !! 2

[1,2,2,3,4]The lists within a list can be of different lengths but they can’t be of different types. Just like you can’t have a list that has some characters and some numbers, you can’t have a list that has some lists of characters and some lists of numbers.

Lists can be compared if the stuff they contain can be compared. When

using <, <=, > and

>= to compare lists, they are compared in

lexicographical order. First the heads are compared. If they are equal

then the second elements are compared, etc.

ghci> [3,2,1] > [2,1,0]

True

ghci> [3,2,1] > [2,10,100]

True

ghci> [3,4,2] > [3,4]

True

ghci> [3,4,2] > [2,4]

True

ghci> [3,4,2] == [3,4,2]

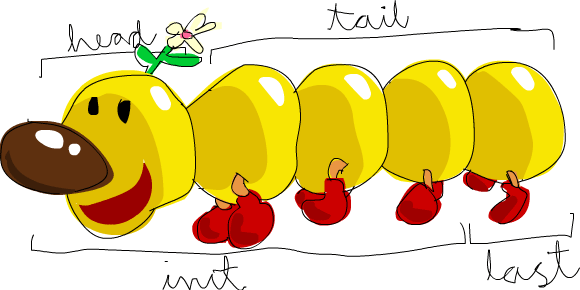

TrueWhat else can you do with lists? Here are some basic functions that operate on lists.

head takes a list and returns its

head. The head of a list is basically its first element.

ghci> head [5,4,3,2,1]

5tail takes a list and returns its

tail. In other words, it chops off a list’s head.

ghci> tail [5,4,3,2,1]

[4,3,2,1]last takes a list and returns its

last element.

ghci> last [5,4,3,2,1]

1init takes a list and returns

everything except its last element.

ghci> init [5,4,3,2,1]

[5,4,3,2]If we think of a list as a monster, here’s what’s what.

But what happens if we try to get the head of an empty list?

ghci> head []

*** Exception: Prelude.head: empty listOh my! It all blows up in our face! If there’s no monster, it doesn’t

have a head. When using head, tail,

last and init, be careful not to use them on

empty lists. This error cannot be caught at compile time, so it’s always

good practice to take precautions against accidentally telling Haskell

to give you some elements from an empty list.

length takes a list and returns

its length, obviously.

ghci> length [5,4,3,2,1]

5null checks if a list is empty.

If it is, it returns True, otherwise it returns

False. Use this function instead of xs == []

(if you have a list called xs).

ghci> null [1,2,3]

False

ghci> null []

Truereverse reverses a list.

ghci> reverse [5,4,3,2,1]

[1,2,3,4,5]take takes a number and a list.

It extracts that many elements from the beginning of the list.

Watch.

ghci> take 3 [5,4,3,2,1]

[5,4,3]

ghci> take 1 [3,9,3]

[3]

ghci> take 5 [1,2]

[1,2]

ghci> take 0 [6,6,6]

[]See how if we try to take more elements than there are in the list, it just returns the list. If we try to take 0 elements, we get an empty list.

drop works in a similar way, only

it drops the number of elements from the beginning of a list.

ghci> drop 3 [8,4,2,1,5,6]

[1,5,6]

ghci> drop 0 [1,2,3,4]

[1,2,3,4]

ghci> drop 100 [1,2,3,4]

[]maximum takes a list of stuff

that can be put in some kind of order and returns the biggest

element.

minimum returns the smallest.

ghci> minimum [8,4,2,1,5,6]

1

ghci> maximum [1,9,2,3,4]

9sum takes a list of numbers and

returns their sum.

product takes a list of numbers

and returns their product.

ghci> sum [5,2,1,6,3,2,5,7]

31

ghci> product [6,2,1,2]

24

ghci> product [1,2,5,6,7,9,2,0]

0elem takes a thing and a list of

things and tells us if that thing is an element of the list. It’s

usually called as an infix function because it’s easier to read that

way.

ghci> 4 `elem` [3,4,5,6]

True

ghci> 10 `elem` [3,4,5,6]

FalseThose were a few basic functions that operate on lists. We’ll take a look at more list functions later.

Texas ranges

What if we want a list of all

numbers between 1 and 20? Sure, we could just type them all out but

obviously that’s not a solution for gentlemen who demand excellence from

their programming languages. Instead, we’ll use ranges. Ranges are a way

of making lists that are arithmetic sequences of elements that can be

enumerated. Numbers can be enumerated. One, two, three, four, etc.

Characters can also be enumerated. The alphabet is an enumeration of

characters from A to Z. Names can’t be enumerated. What comes after

“John”? I don’t know.

What if we want a list of all

numbers between 1 and 20? Sure, we could just type them all out but

obviously that’s not a solution for gentlemen who demand excellence from

their programming languages. Instead, we’ll use ranges. Ranges are a way

of making lists that are arithmetic sequences of elements that can be

enumerated. Numbers can be enumerated. One, two, three, four, etc.

Characters can also be enumerated. The alphabet is an enumeration of

characters from A to Z. Names can’t be enumerated. What comes after

“John”? I don’t know.

To make a list containing all the natural numbers from 1 to 20, you

just write [1..20]. That is the equivalent of writing

[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] and

there’s no difference between writing one or the other except that

writing out long enumeration sequences manually is stupid.

ghci> [1..20]

[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]

ghci> ['a'..'z']

"abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz"

ghci> ['K'..'Z']

"KLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ"Ranges are cool because you can also specify a step. What if we want all even numbers between 1 and 20? Or every third number between 1 and 20?

ghci> [2,4..20]

[2,4,6,8,10,12,14,16,18,20]

ghci> [3,6..20]

[3,6,9,12,15,18]It’s simply a matter of separating the first two elements with a

comma and then specifying what the upper limit is. While pretty smart,

ranges with steps aren’t as smart as some people expect them to be. You

can’t do [1,2,4,8,16..100] and expect to get all the powers

of 2. Firstly because you can only specify one step. And secondly

because some sequences that aren’t arithmetic are ambiguous if given

only by a few of their first terms.

To make a list with all the numbers from 20 to 1, you can’t just do

[20..1], you have to do [20,19..1].

Watch out when using floating point numbers in ranges! Because they are not completely precise (by definition), their use in ranges can yield some pretty funky results.

ghci> [0.1, 0.3 .. 1]

[0.1,0.3,0.5,0.7,0.8999999999999999,1.0999999999999999]My advice is not to use them in list ranges.

You can also use ranges to make infinite lists by just not specifying

an upper limit. Later we’ll go into more detail on infinite lists. For

now, let’s examine how you would get the first 24 multiples of 13. Sure,

you could do [13,26..24*13]. But there’s a better way:

take 24 [13,26..]. Because Haskell is lazy, it won’t try to

evaluate the infinite list immediately because it would never finish.

It’ll wait to see what you want to get out of that infinite lists. And

here it sees you just want the first 24 elements and it gladly

obliges.

A handful of functions that produce infinite lists:

cycle takes a list and cycles it

into an infinite list. If you just try to display the result, it will go

on forever so you have to slice it off somewhere.

ghci> take 10 (cycle [1,2,3])

[1,2,3,1,2,3,1,2,3,1]

ghci> take 12 (cycle "LOL ")

"LOL LOL LOL "repeat takes an element and

produces an infinite list of just that element. It’s like cycling a list

with only one element.

ghci> take 10 (repeat 5)

[5,5,5,5,5,5,5,5,5,5]Although it’s simpler to just use the replicate function if you want some number

of the same element in a list. replicate 3 10 returns

[10,10,10].

I’m a list comprehension

If you’ve ever taken a course in

mathematics, you’ve probably run into set comprehensions.

They’re normally used for building more specific sets out of general

sets. A basic comprehension for a set that contains the first ten even

natural numbers is

If you’ve ever taken a course in

mathematics, you’ve probably run into set comprehensions.

They’re normally used for building more specific sets out of general

sets. A basic comprehension for a set that contains the first ten even

natural numbers is  . The part before the pipe is called the output

function,

. The part before the pipe is called the output

function, x is the variable, N is the input

set and x <= 10 is the predicate. That means that the

set contains the doubles of all natural numbers that satisfy the

predicate.

If we wanted to write that in Haskell, we could do something like

take 10 [2,4..]. But what if we didn’t want doubles of the

first 10 natural numbers but some kind of more complex function applied

on them? We could use a list comprehension for that. List comprehensions

are very similar to set comprehensions. We’ll stick to getting the first

10 even numbers for now. The list comprehension we could use is

[x*2 | x <- [1..10]]. x is drawn from

[1..10] and for every element in [1..10]

(which we have bound to x), we get that element, only

doubled. Here’s that comprehension in action.

ghci> [x*2 | x <- [1..10]]

[2,4,6,8,10,12,14,16,18,20]As you can see, we get the desired results. Now let’s add a condition (or a predicate) to that comprehension. Predicates go after the binding parts and are separated from them by a comma. Let’s say we want only the elements which, doubled, are greater than or equal to 12.

ghci> [x*2 | x <- [1..10], x*2 >= 12]

[12,14,16,18,20]Cool, it works. How about if we wanted all numbers from 50 to 100 whose remainder when divided with the number 7 is 3? Easy.

ghci> [ x | x <- [50..100], x `mod` 7 == 3]

[52,59,66,73,80,87,94]Success! Note that weeding out lists by predicates is also called

filtering. We took a list of numbers and we filtered

them by the predicate. Now for another example. Let’s say we want a

comprehension that replaces each odd number greater than 10 with

"BANG!" and each odd number that’s less than 10 with

"BOOM!". If a number isn’t odd, we throw it out of our

list. For convenience, we’ll put that comprehension inside a function so

we can easily reuse it.

boomBangs xs = [ if x < 10 then "BOOM!" else "BANG!" | x <- xs, odd x]The last part of the comprehension is the predicate. The function

odd returns True on an odd number and

False on an even one. The element is included in the list

only if all the predicates evaluate to True.

ghci> boomBangs [7..13]

["BOOM!","BOOM!","BANG!","BANG!"]We can include several predicates. If we wanted all numbers from 10 to 20 that are not 13, 15 or 19, we’d do:

ghci> [ x | x <- [10..20], x /= 13, x /= 15, x /= 19]

[10,11,12,14,16,17,18,20]Not only can we have multiple predicates in list comprehensions (an

element must satisfy all the predicates to be included in the resulting

list), we can also draw from several lists. When drawing from several

lists, comprehensions produce all combinations of the given lists and

then join them by the output function we supply. A list produced by a

comprehension that draws from two lists of length 4 will have a length

of 16, provided we don’t filter them. If we have two lists,

[2,5,10] and [8,10,11] and we want to get the

products of all the possible combinations between numbers in those

lists, here’s what we’d do.

ghci> [ x*y | x <- [2,5,10], y <- [8,10,11]]

[16,20,22,40,50,55,80,100,110]As expected, the length of the new list is 9. What if we wanted all possible products that are more than 50?

ghci> [ x*y | x <- [2,5,10], y <- [8,10,11], x*y > 50]

[55,80,100,110]How about a list comprehension that combines a list of adjectives and a list of nouns … for epic hilarity.

ghci> nouns = ["hobo","frog","pope"]

ghci> adjectives = ["lazy","grouchy","scheming"]

ghci> [adjective ++ " " ++ noun | adjective <- adjectives, noun <- nouns]

["lazy hobo","lazy frog","lazy pope","grouchy hobo","grouchy frog",

"grouchy pope","scheming hobo","scheming frog","scheming pope"]I know! Let’s write our own version of length! We’ll

call it length'.

length' xs = sum [1 | _ <- xs]_ means that we don’t care what we’ll draw from the list

anyway so instead of writing a variable name that we’ll never use, we

just write _. This function replaces every element of a

list with 1 and then sums that up. This means that the

resulting sum will be the length of our list.

Just a friendly reminder: because strings are lists, we can use list comprehensions to process and produce strings. Here’s a function that takes a string and removes everything except uppercase letters from it.

removeNonUppercase st = [ c | c <- st, c `elem` ['A'..'Z']]Testing it out:

ghci> removeNonUppercase "Hahaha! Ahahaha!"

"HA"

ghci> removeNonUppercase "IdontLIKEFROGS"

"ILIKEFROGS"The predicate here does all the work. It says that the character will

be included in the new list only if it’s an element of the list

['A'..'Z']. Nested list comprehensions are also possible if

you’re operating on lists that contain lists. A list contains several

lists of numbers. Let’s remove all odd numbers without flattening the

list.

ghci> let xxs = [[1,3,5,2,3,1,2,4,5],[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9],[1,2,4,2,1,6,3,1,3,2,3,6]]

ghci> [ [ x | x <- xs, even x ] | xs <- xxs]

[[2,2,4],[2,4,6,8],[2,4,2,6,2,6]]You can write list comprehensions across several lines. So if you’re not in GHCI, it’s better to split longer list comprehensions across multiple lines, especially if they’re nested.

Tuples

In some ways, tuples are like lists — they are a way to store several values into a single value. However, there are a few fundamental differences. A list of numbers is a list of numbers. That’s its type and it doesn’t matter if it has only one number in it or an infinite amount of numbers. Tuples, however, are used when you know exactly how many values you want to combine and its type depends on how many components it has and the types of the components. They are denoted with parentheses and their components are separated by commas.

Another key difference is that they don’t have to be homogenous. Unlike a list, a tuple can contain a combination of several types.

Think about how we’d represent a two-dimensional vector in Haskell.

One way would be to use a list. That would kind of work. So what if we

wanted to put a couple of vectors in a list to represent points of a

shape on a two-dimensional plane? We could do something like

[[1,2],[8,11],[4,5]]. The problem with that method is that

we could also do stuff like [[1,2],[8,11,5],[4,5]], which

Haskell has no problem with since it’s still a list of lists with

numbers, but it kind of doesn’t make sense. But a tuple of size two

(also called a pair) is its own type, which means that a list can’t have

a couple of pairs in it and then a triple (a tuple of size three), so

let’s use that instead. Instead of surrounding the vectors with square

brackets, we use parentheses: [(1,2),(8,11),(4,5)]. What if

we tried to make a shape like [(1,2),(8,11,5),(4,5)]? Well,

we’d get this error:

• Couldn't match expected type ‘(a, b)’

with actual type ‘(a0, b0, c0)’

• In the expression: (8, 11, 5)

In the expression: [(1, 2), (8, 11, 5), (4, 5)]

In an equation for ‘it’: it = [(1, 2), (8, 11, 5), (4, 5)]

• Relevant bindings include

it :: [(a, b)] (bound at <interactive>:1:1)It’s telling us that we tried to use a pair and a triple in the same

list, which is not supposed to happen. You also couldn’t make a list

like [(1,2),("One",2)] because the first element of the

list is a pair of numbers and the second element is a pair consisting of

a string and a number. Tuples can also be used to represent a wide

variety of data. For instance, if we wanted to represent someone’s name

and age in Haskell, we could use a triple:

("Christopher", "Walken", 55). As seen in this example,

tuples can also contain lists.

Use tuples when you know in advance how many components some piece of data should have. Tuples are much more rigid because each different size of tuple is its own type, so you can’t write a general function to append an element to a tuple — you’d have to write a function for appending to a pair, one function for appending to a triple, one function for appending to a 4-tuple, etc.

While there are singleton lists, there’s no such thing as a singleton tuple. It doesn’t really make much sense when you think about it. A singleton tuple would just be the value it contains and as such would have no benefit to us.

Like lists, tuples can be compared with each other if their components can be compared. Only you can’t compare two tuples of different sizes, whereas you can compare two lists of different sizes. Two useful functions that operate on pairs:

fst takes a pair and returns its

first component.

ghci> fst (8,11)

8

ghci> fst ("Wow", False)

"Wow"snd takes a pair and returns its

second component. Surprise!

ghci> snd (8,11)

11

ghci> snd ("Wow", False)

FalseNote: these functions operate only on pairs. They won’t work on triples, 4-tuples, 5-tuples, etc. We’ll go over extracting data from tuples in different ways a bit later.

A cool function that produces a list of pairs: zip. It takes two lists and then zips them

together into one list by joining the matching elements into pairs. It’s

a really simple function but it has loads of uses. It’s especially

useful for when you want to combine two lists in a way or traverse two

lists simultaneously. Here’s a demonstration.

ghci> zip [1,2,3,4,5] [5,5,5,5,5]

[(1,5),(2,5),(3,5),(4,5),(5,5)]

ghci> zip [1 .. 5] ["one", "two", "three", "four", "five"]

[(1,"one"),(2,"two"),(3,"three"),(4,"four"),(5,"five")]It pairs up the elements and produces a new list. The first element

goes with the first, the second with the second, etc. Notice that

because pairs can have different types in them, zip can

take two lists that contain different types and zip them up. What

happens if the lengths of the lists don’t match?

ghci> zip [5,3,2,6,2,7,2,5,4,6,6] ["im","a","turtle"]

[(5,"im"),(3,"a"),(2,"turtle")]The longer list simply gets cut off to match the length of the shorter one. Because Haskell is lazy, we can zip finite lists with infinite lists:

ghci> zip [1..] ["apple", "orange", "cherry", "mango"]

[(1,"apple"),(2,"orange"),(3,"cherry"),(4,"mango")]

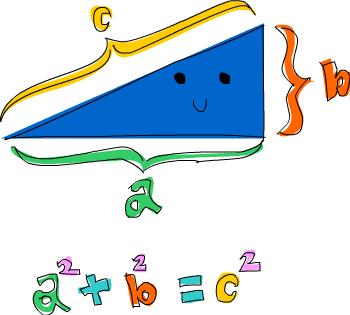

Here’s a problem that combines tuples and list comprehensions: which right triangle that has integers for all sides and all sides equal to or smaller than 10 has a perimeter of 24? First, let’s try generating all triangles with sides equal to or smaller than 10:

ghci> triangles = [ (a,b,c) | c <- [1..10], b <- [1..10], a <- [1..10] ]We’re just drawing from three lists and our output function is

combining them into a triple. If you evaluate that by typing out

triangles in GHCI, you’ll get a list of all possible

triangles with sides under or equal to 10. Next, we’ll add a condition

that they all have to be right triangles. We’ll also modify this

function by taking into consideration that side b isn’t larger than the

hypotenuse and that side a isn’t larger than side b.

ghci> rightTriangles = [ (a,b,c) | c <- [1..10], b <- [1..c], a <- [1..b], a^2 + b^2 == c^2]We’re almost done. Now, we just modify the function by saying that we want the ones where the perimeter is 24.

ghci> rightTriangles' = [ (a,b,c) | c <- [1..10], b <- [1..c], a <- [1..b], a^2 + b^2 == c^2, a+b+c == 24]

ghci> rightTriangles'

[(6,8,10)]And there’s our answer! This is a common pattern in functional programming. You take a starting set of solutions and then you apply transformations to those solutions and filter them until you get the right ones.